The days of our lives

When we look backwards and think of what we remember, we know that all days in the past were not equal. But is this really true?

The sun always rises. (Photo by Marc Kleen on Unsplash)

The sun always rises. (Photo by Marc Kleen on Unsplash)

Memory is endlessly fascinating.

I’ve written before about money memories, and how they form. But never mind the specifics of money for a moment and just consider memory more broadly.

Think of when you were five years old, or 10, or 20. What do you remember?

We don’t remember whole scenes or occasions. We don’t remember complete events. We don’t remember the start to finish of anything, even days that we might think of as vital days that made us who we are right now, today.

Instead we remember slivers of things. Moments. Flashes.

My first memory is of the football World Cup in 1982. All I remember is color. My mind tells me now that it was Brazil vs Italy, but I have no way of knowing whether that’s just a story I’d like to believe (the Brazil-Italy game of 1982 being an all-time classic). But I do remember color: the green of the pitch, the yellow and blue of the jerseys — or is that just my Brazil-Italy wishful thinking? I think I remember the noise too, of the commentary coming through over crackling airwaves, of the fans in the stands, but none of the specifics are available to me.

Later, I remember walking up the wooden steps of the school on my first day there when I was four. I presume my mother was holding my hand, but I have no memory of that. It’s just a photograph, but one without any details. It’s not even clear enough to be grainy. I remember another moment, eight years later, on the last days in the same primary school, and a boy — I don’t remember who, even thought it must have been someone I’d shared a classroom with for years — singing “We’ll be out of this kip on Tuesday! Out of this kip on Tuesday!”

(“Kip”, in Irish colloquial slang, means a “dump”.)

I remember lying in a sleeping bag on a mattress on a floor in a Dublin house, beside my first serious girlfriend somewhere around the day we broke up. I was about 21. I don’t remember anything else. (I remember that I remembered her 10-digit phone number for years afterwards, and as I think now, those ten digits again hover into view.)

I remember the first moment I locked eyes with my wife. I know love at first sight exists, because my life has been governed by one split second moment for more than 20 years now.

I remember holding my daughter on the day she was born. I remember, three years later, the morning my son was born, but I hate the fact that I don’t remember holding him. He was born at 5.30am on a Monday and what I remember from that morning, of all things, is that throughout my wife’s short few hours of labor a tiny TV in the corner of the ward was silently showing a live American football NFL game.

There are countless days I don’t remember.

I say all this just to remind myself, and perhaps you too, that all days in our memory are not equal.

And even more importantly, to remind myself that if all the days in the past were not equal, then of course all the days of the future — including every present moment we will ever have — will not be equal either.

We always feel in the present moment, even if we don’t have the language, the mental acuity or the emotional maturity to pinpoint that feeling.

We can also remember something about how we felt. How we felt in those past present moments is a key ingredient in the memories that remain available to us now.

How might we use this knowledge — the knowledge that we feel in the present moment, and that how we felt in past present moments greatly influence the quality of our memories — to show up differently in our future present moments?

If it’s possible to remind yourself about the future — and I think it is, because that’s the entire premise for this essay — perhaps the most important reminder we must bring to the surface, and keep close at hand, is this:

The present moments we experience in the future will come and go. If we are lucky, they will bring both great joy and great difficulty. The great difficulty will be intricately intertwined with the great joy. It’s impossible to experience great joy without experiencing great difficulty, because it’s the difficulty that gives meaning to the joy. What matters most is that we do the necessary work within our minds: first, to acknowledge the difficult days when they come and do what we can to limit their influence, to stem their flow; and second, to fully appreciate the joyful ones when they come.

We know that all days in the past were not equal.

So we must know that all days in the future will not be equal.

This should give us solace and encouragement for difficult days, and for the slow and boring ones too, because all those days are just another step on the way to the days that will bring true joy, peace and the new memories we will want to take forward for the rest of our lives.

But, a small counterpoint.

(The physicist Nils Bohr said, “the opposite of a profound truth is another profound truth”. With every piece I write I’m aiming to get as close to truth as possible. Whether any of the truths I happen upon amount to anything profound is not for me to say.)

Just because all days in the past were not equal, and because we know that all days in the future will not be equal, doesn’t mean that all days — even the nondescript ones — are not important.

The days I don’t remember also formed me and carved out the life I have now just as much as those I do. They must have done. It was their quality of forgettable-ness that was formative. They were formative in good ways — skills slowly built up, work steadily done, relationships cultivated over years and decades. And they were formative in bad ways too. I’m not sure anybody enjoys the process of reflecting on the pattern of bad days, bad decisions, opportunities allowed to slip past, relationships allowed to go distant or fester, all of which which together add up to an outcome you have now and do not want.

It is necessary, though, to reflect on our own agency on our good days and bad ones. As Jerry Colonna, the soft-spoken but steely leadership coach and author I was lucky enough to chat with on Zoom during the pandemic, puts it:

“How am I complicit in creating the circumstances I say I don’t want?”

That complicity lies in all the forgettable days of the past.

That complicity will also come in all the forgettable, difficult or just boring days of the future.

What we do on the forgettable, difficult and boring days cultivates the life we will have years or decades from now.

Thinking in seasons might help. There are always ups and downs. There is always decay, death, rebirth and regrowth, and not just in organic matter. And because we know there’s always decay-death-rebirth-regrowth, we must know that all the difficult days are necessary ones in that cycle.

It’s true that all we ever really have is this moment, today, and how we choose to experience it.

It’s true also that all those individual todays, forgettable or stirring, eventually pale into insignificance and the longer timeframe of the collective is what creates our present reality.

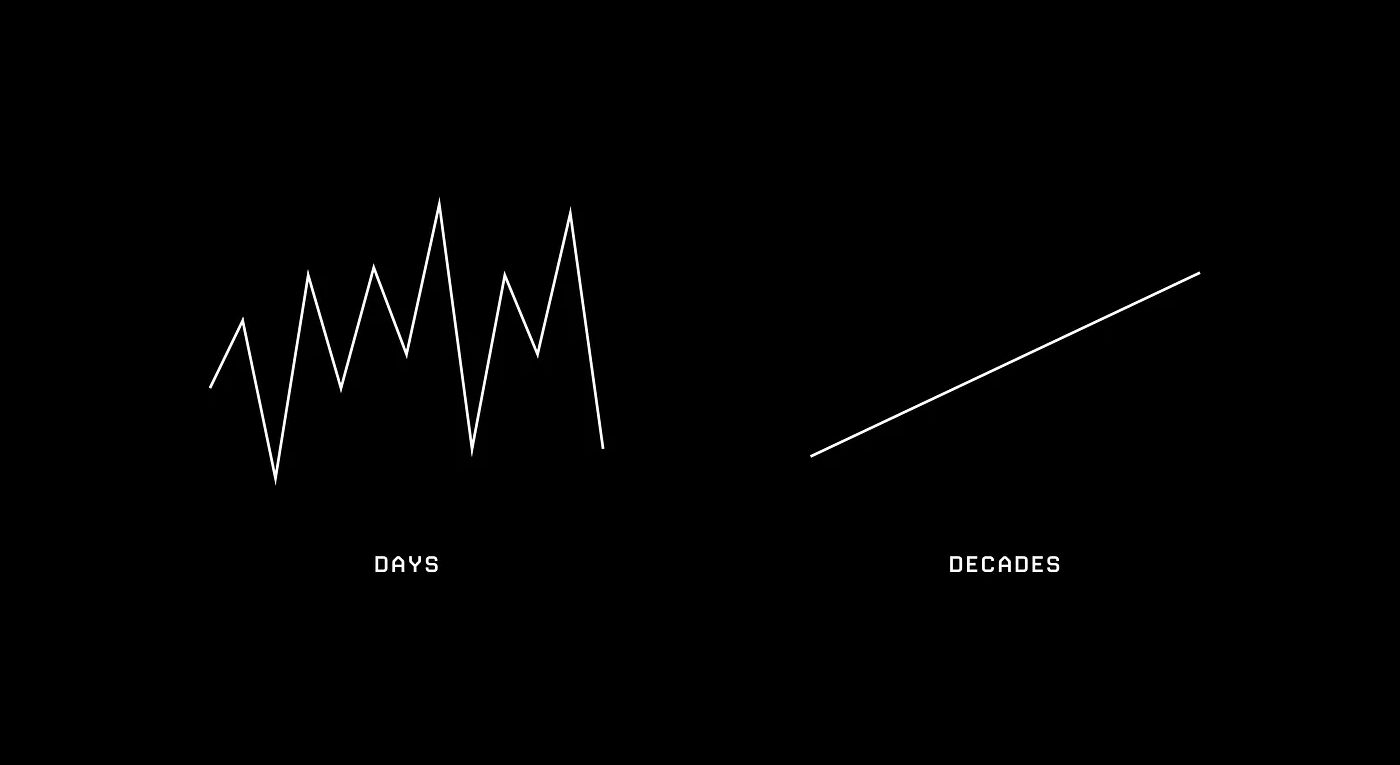

To remind me of everything I’ve tried to work through here, this visual, by digital entrepreneur and visual designer Jack Butcher, of an idea by Carl Richards (aka Behavior Gap), has been my screensaver for years.

Thanks for reading.